Back in 2005, various political and religious leaders suggested that Hurricane Katrina, which killed 1,836 people, was sent as a divine retribution for the sins of New Orleans, or of the South, or of the United States as a whole for that matter. Ray Nagin, who was New Orleans Mayor at the time is said to have asserted in a speech addressing the effects of Hurricane Katrina, “Surely God is mad at America.” Various different reasons were given for God’s wrath. Some victims of the disaster also made attributions to supernatural causes: that they were being punished for their sins, or that God was testing them, or even that the event was “the work of Satan.”

Less than two weeks after Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, my old whipping boy, Pat Robertson, implied on a broadcast of The 700 Club that the hurricane was God’s punishment in response to America’s abortion policy. He suggested that the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the disaster in New Orleans “could… be connected in some way.”

Pro-Life activist Steve Lefemine expressed a similar view, stating that “In my belief, God judged New Orleans for the sin of shedding innocent blood through abortion…. Providence punishes national sins by national calamities…. Greater divine judgment is coming upon America unless we repent of the national sin of abortion.”

Gerhard Maria Wagner, briefly an auxiliary bishop of Linz, Austria attributed Hurricane Katrina to God’s ire caused by the town’s reputation for lax sexual behavior, claiming that the hurricane destroyed brothels, nightclubs and abortion clinics: “It’s no coincidence that in New Orleans all five abortion clinics as well as night clubs were destroyed.”

Evangelist John Charles Hagee linked the hurricane to a gay pride event known as “Southern Decadence Day,” which was to have been held in the town’s French Quarter a few days after the hurricane hit. He said, “I believe that New Orleans had a level of sin that was offensive to God, and they are – were – recipients of the judgment of God for that. The newspaper carried the story in our local area, that was not carried nationally, that there was to be a homosexual parade there on the Monday that the Katrina came.” In rebuttal, About.com’s Urban Legends and Folklore article entitled “Hurricane Katrina: God’s Punishment for a ‘Wicked’ City?” points out that the hurricane occurred before the parade and that the French Quarter was one of the least devastated parts of the city.

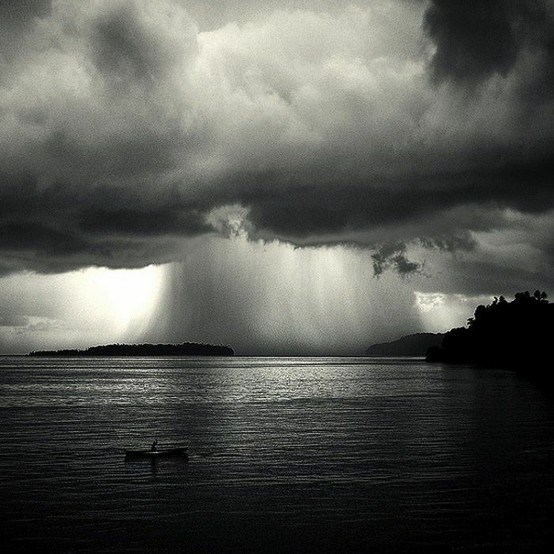

All of the above voices were giving expression to a major tenet in a pre-Copernican God theology that finds ample space in the pages of the Bible. Why do you think there was a flood in the time of Noah? According to the Bible, the flood was sent by God to punish people for their sins. Consistent with this biblical lesson, natural disasters such as floods, earthquakes, tornadoes, Tsunami waves and droughts have throughout history been interpreted as a divine response to a real or imagined human failure. People prayed for weather changes and accompanied those prayers with promises of repentance and a pledge to future actions more pleasing to God.

“We must ask God to stop these rains,” said General George Smith Patton Jr. just before the famous Battle of the Bulge during World War Two. He continued, “These rains are that margin that hold defeat or victory. If we all pray…it will be like plugging in on a current whose source is in Heaven. I believe that prayer completes that circuit. It is power.” The result of this statement was a card with a prayer written by the Head Chaplain of Patton’s Third Army and a Christmas Greeting printed on the reverse side that was distributed to all troops under Patton’s command. It read: “Almighty and most merciful Father, we humbly beseech Thee, of Thy great goodness, to restrain these immoderate rains with which we have had to contend. Grant us fair weather for Battle. Graciously hearken to us as soldiers who call upon Thee that, armed with Thy power, we may advance from victory to victory, and crush the oppression and wickedness of our enemies and establish Thy justice among men and nations.”

General Patton believed God favored the Allies and hated the Nazis. For Patton, since God was assumed to live just above the sky, divine direction of the weather was easy to imagine.

This religious rhetoric permeates our culture on many levels. It is reflected by the fact that many people still view sickness as punishment. “Why did this happen to me?” is a familiar refrain falling from the lips of the ill. When I was chaplain in a major hospital in Baltimore, my usual response to such a question was: “Why not you? Are you somehow unlike the rest of us and immune from suffering?” Now I was not trying to be insensitive or callous, but simply to remind the person that no one is exempt from some form of suffering in this life, not even Jesus. “Why me” is the wrong question because rain falls on the just and the unjust alike and bad things do happen to good people.

We see this same mentality being employed today by television evangelists, among athletes, and in the words of many people in public life. For example, modern athletes seem to believe the God above the sky directs their fortunes. I see an athlete making the sign of the cross before stepping into the batter’s box, or up to the free throw line. I see others point to the sky in gratitude to the God who helped them strike out an opponent, hit a home run, or kick a winning field goal. (I did not know that God was such a sports fan!)

This similar theology also penetrates the way tragedies are interpreted. Survivors, who climb out of an airliner crash or escape a subway bombing, or walk away from a horrific traffic accident, seem almost invariably to assume that God has spared their lives. The unspoken implication, of course, is that those who died either deserved it or that God had no special plan for them beyond premature death.

What is it that gives such power to these primitive ideas that athletes or presumably well-educated people in public life, or just average people still think and talk this way? Is some basic human need met by this theology? Does pious rhetoric blunt our thinking processes? Or does this tenacious idea simply reflect an ever-present but seldom faced part of our humanity?

I suspect that part of the answer to those questions is that to be human is to yearn for some assurance that we are not alone in this vast and impersonal world. As human beings, we are the only creatures whose minds are sufficiently developed to embrace the vastness of the universe. As humans, we alone understand the meaning of time. As humans, we can both anticipate impending disasters and embrace the fact that we will die. Such ability is one of the consequences of being human and as a result humans will always be chronically anxious. Anxiety is one of the byproducts of self-consciousness. Add fear to this anxiety and you have the conditions that seem to compel we humans to create a divine supernatural God figure powerful enough to be our protector. This deity must not be limited as we are, since such restrictions would not give us security. Human beings never seem to escape that childhood memory of having an apparently all-powerful parent figure taking care of them. Finding ourselves alone as adults, we place a divine parent figure called God in the sky where, unseen but ever watchful, this being can and will look after us. We even call this parent figure, “Father.” Then we ascribe to this Father-God the qualities that we humans lack. Since we are mortal, God must be immortal. Because we are powerless, God must be all-powerful. And so on. Once we have defined God this way, we begin to relate to this God exactly the way children relate to their parents. We bargain with God, make our requests known to God, manipulate God, flatter God into getting our way, seek to win God’s favor by keeping God’s rules, confess to God when we fail and – and as our parents rightly taught us – always remember to say “thank you” so that God will reward us for being good and grateful children.

Not surprisingly, this supernatural theistic religion is still very much alive in our churches because claiming the ability to interpret how God will act and what will please the Holy One is both the source of ecclesiastical authority and control and the cause of our own spiritual immaturity. From this perspective, we view sickness and tragedy as signs of divine anger, reflecting the world we have created, with ourselves living at the center of it and God understood as the one who keeps things fair as a good parent should.

The result of this religious mentality might well be temporarily comforting, but ultimately it is destructive. For instance, when the infamous Black Death, one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, swept through Europe and the Middle East in the fourteenth century, many thought that the reason for such a disaster was the wrath of God. What was the cause of God’s wrath? At the time, the most obvious answer was the culprit was that the sinfulness of the people, so a movement arose known as the “Flagellants” – religious zealots who demonstrated their religious fervor and sought atonement for their sins by vigorously whipping themselves in public displays of penance. Their hope was that if they punished themselves sufficiently, God would withdraw the punishing “black death.” The second answer put forth was that God was angry because Europe’s Christians had tolerated infidels. Responding to that premise, Christians proceeded to persecute Jews in a frenzy of murderous anti-Semitism. Jews were reviled and accused in all lands of having caused the Black Death through the poison that they were said to have put into the water and the wells. For this reason, Jews were burned all the way from the Mediterranean to Germany.

So, too, when unexplained mysteries baffled the citizens of Salem, Massachusetts in the late seventeenth century, citizenries responded by executing women they deemed to be witches and the agents of Satan, who, they concluded, had caused their distress. And, to come full circle, when Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans in 2005, it was God’s punishment for the wickedness of the people of that great city that unleashed the devastating hurricane.

Do we find this idea of a wrathful God comforting?

Ironically enough, there does appear to be a far deeper connection between human behavior and natural disaster than our popular rhetoric imagines. Some natural disasters, such as the collision of tectonic plates that create Tsunami waves are just that, natural disasters. They are not a response to anyone’s behavior. Other disasters, however, are connected with our human behavior, but not in the old moralistic sense of “God’s going to get you for this.”

We are, for example, experiencing today changing weather patterns that reflect impending environmental disasters. They result not from an angry deity, but from such things as irresponsible human breeding habits that have led to overpopulation and the resulting exhaustion of many of the earth’s resources. We have cut down the rain forests, polluted the air we breathe and the water we drink. Our behavior has led to global warming, acid rain, the melting of the polar icecaps and the resulting dramatic changes in the weather patterns of our world. These present and pending disasters are nature’s way of saying that our rape of the earth has dire consequences. These disasters are the result of a humanity that has not yet embraced the fact that the world is not an enemy that we must conquer and subdue as if we are not a part of it. We are all on this spaceship called Earth.

These calamities are the result of our conceptualizing God as separated from this world, isolated in the sky, and then endowing this God with symbols of parenthood that allow us to remain irresponsible children who cannot see beyond the level of our own self-centered need for comfort and security.

But as hard as it is for some to fathom, there is no deity in the sky who will send out a divine Electrolux to gobble up the human waste that now warms our atmosphere. There is no heavenly filtering system through which we can recycle the water of our rivers, lakes and oceans. As much as many politicians may deny this fact, in today’s world there is no scapegoat other than ourselves upon whom we can heap the blame for our rapid environmental degradation. Global warming is real whether we like it or not. That is why globally, the mercury is already up more than one degree Fahrenheit, and even more in sensitive Polar Regions. And the effects of rising temperatures are not waiting for some far-flung future. They are happening right now. Signs are appearing all over, and some of them are surprising. The heat is not only melting glaciers and sea ice; it is also shifting precipitation patterns and setting animals on the move. Current changes and future predictions include:

- Ice is melting worldwide, especially at the Earth’s poles. This condition includes mountain glaciers, ice sheets covering West Antarctica and Greenland, and Arctic sea ice. The Adélie penguins on Antarctica have seen their numbers dwindle from 32,000 breeding pairs to 11,000 in thirty years.

- Sea level rise became faster over the last century. Precipitation (rain and snowfall) has increased across the globe, on average. Sea levels are expected to rise between seven and twenty-three inches by the end of the century and continued melting at the poles could add between four and eight inches. Floods and droughts will become more common. Rainfall in Ethiopia, where droughts are already common, could decline by ten percent over the next fifty years. Hurricanes and other storms are likely to become stronger.

- Less fresh water will be available. If the Quelccaya ice cap in Peru continues to melt at its current rate, it will be gone by 2100, leaving thousands of people who rely on it for drinking water and electricity without a source of either.

- Some butterflies, foxes, and alpine plants have moved farther north or to higher, cooler areas. Spruce bark beetles have boomed in Alaska thanks to twenty years of warm summers. The insects have chewed up four million acres of spruce trees.

- Species that depend on one another may become out of sync. For example, plants could bloom earlier than their pollinating insects can

- become active. Some diseases will spread such as malaria carried by mosquitoes.

- Ecosystems will change – some species will move farther north or become more successful; others will not be able to move and could become extinct. Perhaps you have not noticed, but with less ice on which to live and fish for food, polar bears have become considerably skinnier. If sea ice disappears, the polar bears will disappear as well.

These calamities are not the result of a wrathful God punishing humankind for some supposed misdeeds; they are the direct result of we humans continuing to act with childlike irresponsibility because we have not yet embraced the idea that there is no supernatural God in the sky who will protect us even from ourselves.

Sinners in the hands of an angry God? Eighteenth century Calvinist preacher Jonathan Edwards may have thought so, but I believe the time has come for our understanding of God to mature. Our “heavenly father” definition of God acts to relieve us of responsibility. Our greatest religious fear is that if God is not this Supernatural Being in the sky, then there is no God. Atheism is, we think, the only alternative to theism. But it is not. That is the boundary over which religious people fear to walk. But walk they must.

Episcopal Bishop John Shelby Spong helps us here when he writes: “Suppose we define God as the Source of Life, so that our worship demands that we cooperate with all of nature rather than trying to conquer it for our own benefit. Suppose God is defined as the Source of Love, so that our worship enables us to journey beyond the limits of our fear to embrace all that is. Suppose God is defined as the Ground of Being so that our worship relates us to a holiness that permeates all that is. That is what we need to understand before we human beings can grow up and accept responsibility for our world.”

So the next time you hear or see a political figure, or a televangelist, or an athlete, or a pope, or any other person act as if God is responsible for the weather, or for sickness, or for our victories and defeats, or for whether we kick a field goal or not, recognize it for what it is: the action of a human being who above all else needs to mature spiritually. As Saint Paul wrote in his letter to the church at Corinth: “When we were children, we thought and reasoned as children do. But when we grew up, we quit our childish ways.” – I Corinthians 13:11 (Contemporary English Version)